History

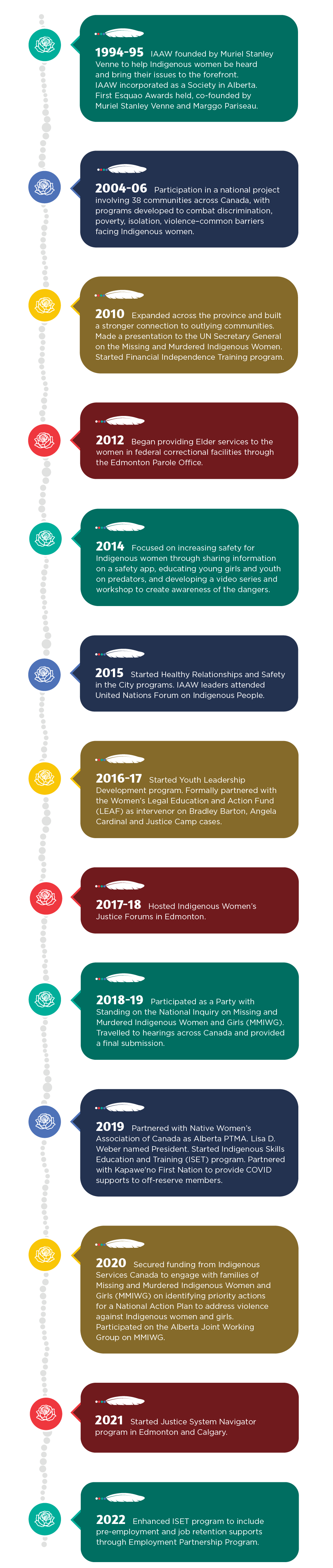

Muriel created an organization that helped Indigenous women be heard and that brought their issues to the forefront. She wanted to celebrate the spirit and resiliency of Indigenous women in Alberta. Muriel wanted Indigenous women to know there was an organization in Alberta and Canada that would stand up for them. The Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women was incorporated as a Society in Alberta in September of 1995 with a team of strong women “who weren’t going to take it anymore.”

The Esquao Awards were launched by Muriel and Marggo Pariseau in 1995, recognizing Indigenous women for their significant accomplishments in their communities. This long-running event is now the single largest recognition event of Indigenous women in Canada.

The majority of advocacy cases taken on by Esquao were a result of human rights violations. In the late 1990s, staff designed The Rights Path-Alberta booklet and video which listed the human rights in 13 protected areas in plain language to educate people on their human rights. Esquao leaders attended United Nations Forum on Indigenous People in 2009 and again in 2015.

A presentation was made to Secretary General in 2010 on the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, in which the names of the women missing and murdered with no one charged was highlighted. Esquao partnered with the Aboriginal Commission on Human Rights and Justice to develop the Social Justice Awards to honour non-Indigenous allies who were working to advance justice for Indigenous people.

Indigenous women are over-represented as victims of violence. Since 2014, Esquao has focused on increasing safety for Indigenous women, by sharing information on a safety app, educating young girls and youth on predators, and in the development of a video series and workshop to create awareness of the dangers and connect women to community resources.

As Indigenous women represent almost half of the women in federal correctional facilities and the majority of women in provincial jails, we have provided Elder services to the women in federal correctional facilities through the Edmonton Parole Office since 2012.

Remembering

Muriel Stanley Venne CM, AOE, BA (Hon.)

1937 – 2024

Thank you Muriel for serving as a guide and role model, for living the value of service, and for your unwavering commitment to your family, community and to justice!

Muriel Stanley Venne’s activism started in the early 1970s and a pivotal moment came in 1973 when Premier Peter Lougheed named Muriel as one of the first appointees to the Alberta Human Rights Commission, where she later served as chair. Muriel went on to create The Rights Path – Alberta, a resource booklet on Human Rights as it applies to Indigenous people.

In 1994, Muriel founded Esquao, the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women, a provincial organization dedicated to amplifying the voices of Indigenous women on various social and economic issues. Vocal and sometimes controversial, her commitment never wavered, and through Muriel’s leadership and vision, Esquao transformed from a modest not-for-profit operation into a thriving entity with capital assets and millions of dollars in programming for Indigenous women throughout Alberta.

In 1995, Muriel co-founded the Esquao Awards with her longtime friend, Marggo Pariseau, to honour Indigenous women in Alberta for their accomplishments. The Esquao Awards have grown to be the single largest recognition event of Indigenous women in Canada.

Muriel devoted decades of work to ensure Indigenous women are treated with dignity, know their rights, and have resources to live healthy and independent lives. She saw herself in every woman who came to her for advice saying, “they are me” and truly meant it.

Muriel Stanley Venne was the recipient of numerous awards and honours over her lifetime, including: the Alberta Human Rights Award in 1998; the National Aboriginal Achievement Award for Justice and Human Rights in 2004; being named a Member of the Order of Canada for her work in bringing awareness of the violent deaths of Aboriginal women in 2005; the Governor General’s Award in Commemoration of the Persons Case in 2005; the Alberta Government Centennial Medal in 2005; Distinguished Citizen Award from Grant MacEwan University in 2010; the Queen’s Commemorative Medals in 2002 and 2012; in 2017, the Muriel Stanley Venne Provincial Centre was the first Alberta government building named after a Métis woman; and she was admitted to the Alberta Order of Excellence in 2019, the highest honour the Province of Alberta can bestow on a citizen.

Muriel once said, “The thing I was trying to change was to have people see my family and my people with love and caring. I really wanted people to be equal – with no hierarchy – just the right to be who you are and for women to be respected.”

Remembering

Marggo Pariseau

1952 – 2025

Mentor, Kokum and Auntie—from the earliest days of the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women (IAAW), Marggo Pariseau dedicated herself to honouring, uplifting and supporting Indigenous women in her work.

As vice-president of IAAW, Pariseau made a significant impact on the lives of many Indigenous women through her advocacy, leadership and service.

Thank you Kokum Marggo for your kindness, wisdom and mentorship, and for being a shining light for Indigenous women. Your legacy will continue to set an example of resilience and compassion.